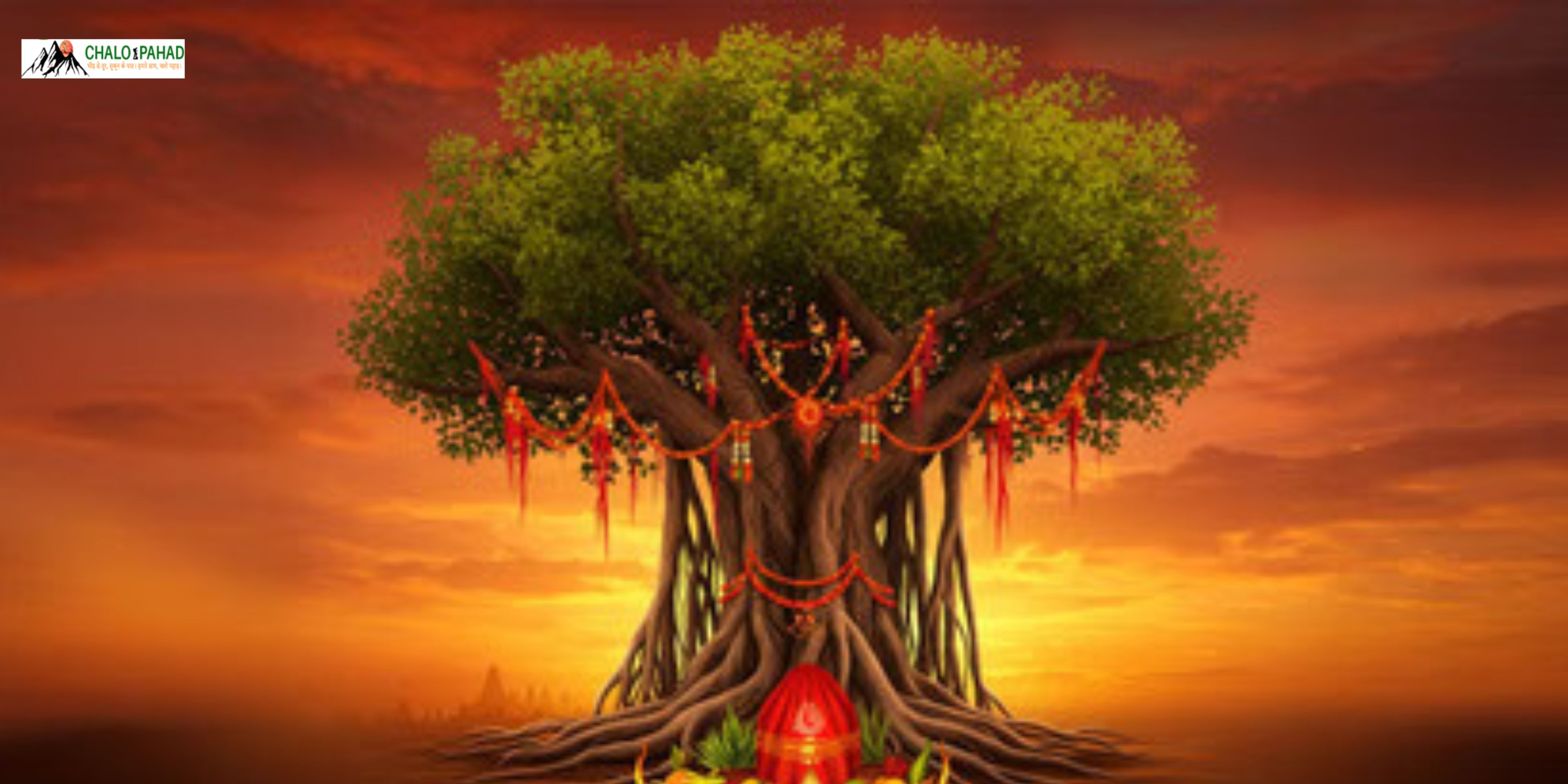

If you walk into a village courtyard in Uttarakhand on a warm day in the month of Jyeshtha (ज्येष्ठ), you can hear laughter mixed with chanting. Women in bright saris, purple glass bangles on their wrists, gather close to an old banyan tree (वट वृक्ष). Some deliver baskets full of culmination, vegetation, and a small diya (दीया). Others maintain cotton threads, neat coils geared up to be tied around the trunk. This is Vat Savitri (वट सावित्री), a competition that looks simple from the outside; however, it contains centuries of remembrance within it.

The Story That Breathes Through Time

The pageant stands on one tale, the story of Savitri (सावित्री) and her husband Satyavan (सत्यवान). Children in the hills nevertheless listen to it from their grandmothers. Savitri, strong-willed and clever, chose Satyavan even after saints warned she would lose him within a year.

One summer afternoon, within the woodland, Satyavan fell while slicing wood. Yamraj (यमराज), the god of demise, seemed. Most would have broken down, but Savitri walked with Yamraj, each step, her phrases steady. She asked for advantages, no longer for herself, but for her in-laws, for her own family’s future. Finally, together with her wit and devotion, she requested Satyavan’s existence back. Yamraj agreed.

This story is not told like a distant myth. Women repeat it as if it happened yesterday, as if Savitri still walks these forests.

Morning in the Villages

On Vat Savitri day, villages wake earlier than usual. The air smells of wet soil, as women sprinkle water in their courtyards earlier than dawn. The sound of bangles (चूड़ियाँ) and the gentle rustle of saris comply with. Many girls fast, nirjala vrat (निर्जला व्रत), with out even water, till the puja ends.

By mid-morning, small organizations stroll to the banyan tree. In some locations, the tree stands near a temple, its roots wrapping low like ropes. In others, it's far at the brink of an area, sheltering vacationers and farm animals alike. Children chase each other around the trunk even as their moms prepare the thalis (थाली) with sindoor (सिंदूर), akshat (अक्षत – unbroken rice), plant life, end result, and a small diya.

As one lady starts to recite the tale of Savitri and Satyavan, the others concentrate, nodding. Some hum folks songs (लोकगीत) they found out as girls. The complete scene feels like a blend of devotion and day-to-day existence.

The Rituals

The vital act is on foot across the banyan tree. Women circle it seven times, tying cotton threads (सूत्र) around the trunk. Each step is a prayer, each knot a want. Some whisper, some stay silent. A few near their eyes, lips transferring with unstated phrases.

The banyan itself holds deep that means. With roots that spread wide and branches that outlive generations, it stands as an image of stability (स्थिरता) and immortality (अमरता). People say the tree holds the presence of the trinity, Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesh (ब्रह्मा, विष्णु, महेश), all together in one region.

After the circling, girls offer the end result and water, mild diyas, and bow their heads. Only then do they go back home, regularly breaking their speed by touching the feet of elders first.

A Scene from Daily Life

Picture this: underneath the banyan’s color, ladies take a seat for a while, their baskets beside them. One adjusts her sari, and some other laughs at a neighbor’s shaggy dog story. Children squat nearby, trying to draw circles in the dust with twigs. An aged grandmother tells the story again, her voice slow but company, at the same time as younger ladies listen in half attention, half distraction.

The sound of temple bells drifts from a distance. The heady scent of incense (अगरबत्ती) mixes with the earthy fragrance of roots. In that moment, the banyan tree feels much less like a plant and more like an elder itself, searching, listening, maintaining stories.

Food and Evening Calm

When the rituals are complete and the quick is damaged, houses fill with the smell of food. Kitchens put together easy meals, dal (दाल), mandua rotis (मंडुवा रोटी), perhaps aloo ke gutke (आलू के गुटके) spiced with jakhya (जाख्या). For dessert, a few families put together kheer (खीर), a rice dish simmered in milk and sweetened with jaggery.

By evening, courtyards glow with diyas. Women, worn-out but happy, sit down collectively with cups of chai. The speaker often shifts from Savitri’s tale to normal topics, crop fees, youngsters’ tests, and news from relatives working in cities. The competition does not take a seat apart from life; it sits within it.

Why It Still Matters

To some, Vat Savitri may also appear to be a woman’s ritual tied to the beyond. But in case you watch carefully, it's far greater than that. It is an afternoon of strength (शक्ति), of remembering that love and determination can bend even fate.

For girls, it's also a moment of networking. In villages wherein days regularly pass in isolation, operating fields, fetching water, and cooking, Vat Savitri brings them together. They sing, they pray, they speak. The banyan tree becomes a meeting area, now not only a symbol.

Even in towns, where there may not be old trees, women still observe the vrat. Some use small branches, others even symbolic images. What matters is the intent, not the scale.

Seasons and Symbols

Vat Savitri falls in the hottest month, Jyeshtha (ज्येष्ठ), when the sun blazes and shade is rare. That too feels symbolic. Just as the banyan gives shelter in summer, Savitri gave shelter to her husband against fate.

The banyan does not shed its leaves quickly, nor does its shade disappear. It stands constant. That is what the vrat reminds families, to stand steady, to remain rooted, to endure.

Closing Thought

Vat Savitri (वट सावित्री) is not a festival of lights or loud processions. It is quieter, but no less powerful. It lives in the hands that tie threads around a tree, in the lips that whisper prayers, in the patient steps of women circling roots.

The story of Savitri and Satyavan is not only about a wife’s devotion. It is about courage, patience, and the will to stand strong even when everything seems lost.

So when you see women under a banyan tree on this day, don’t just see a ritual. See the centuries that flow through it. See the faith that turns myth into memory. See the shade of a tree that holds more than roots; it holds lives, hopes, and prayers.